Hermits, Monks, and Friars: What's the Difference?

They all wear religious habits, usually hooded robes. They all live lives centered on prayer and dedicated to God alone. They are all called “brother” or “father.” But they’re not all the same. What’s the difference between a hermit, a monk, and a friar?

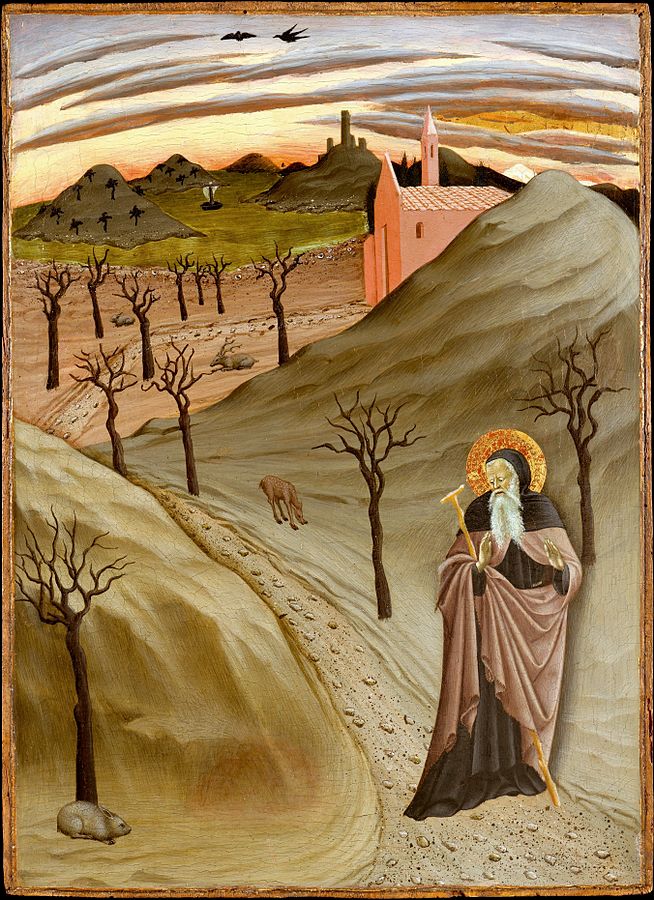

St. Anthony of Egypt, by the Master of the Osservanza

Hermits

The vocation of a hermit is the most ancient form of consecrated life. Sometimes called the eremitical life, this vocation first gained popularity among the Desert Fathers in the first 500 years of Christianity. The most famous of these early hermits was St. Anthony of Egypt, who sold all his possessions and went to live alone in the Egyptian desert in the late 3rd century. Many men (and some women) followed his example, building small hermitages in the desert and devoting themselves to a life of deep prayer, solitude, and asceticism (fasting and penance). Some hermits were completely isolated; others formed loose communities in which younger hermits put themselves under the guidance of seasoned spiritual masters. Today, both kinds of hermits still exist in the Church, in the following forms:

Diocesan hermits, who profess poverty, chastity, and obedience into the hands of their diocesan bishop, and live an eremitic rule of life approved and guided by the bishop. This ancient form of consecration was reintroduced after Vatican II; the regulations for it are given in Canon 603 of the Code of Canon Law.

Religious hermits, who are part of a community of hermits that live a life of intense solitude and prayer while still professing a common form of life. Examples of these would be the Camaldolese and Carmelite Hermits.

St. Benedict, by Fra Angelico

Monks

As the Early Church developed, some communities of hermits became more structured and communal. Instead of living in individual hermitages, the brothers lived in large religious houses that came to be called monasteries or abbeys. Their contemplative lives were less focused on solitude and more focused on a communal life, which meant owning all goods in common, chanting the psalms together, and following a common rule. This communal way of life was called cenobitic, as opposed to eremitic, and its adherents were called monks.

The monastic rule, a document that lays out the monks’ way of life, is an extremely important part of cenobitic life. Many bishops and abbots wrote rules for monasteries, and some of these are still in use today: the Rule of St. Basil, the Rule of St. Augustine, and the Rule of St. Benedict are a few of the most ancient and proven monastic rules. One key aspect of monastic life is a vow of stability, which means that the monks live and work in the same monastery for life.

By the early Middle Ages, monastic life formed part of the core of Christendom. A monastery usually stood at the heart of every medieval town. The monks valued education, literature, and science, founding universities and building libraries. Their theological insights came from lives of contemplation, grounded in Sacred Scripture. They championed developments in sacred art, music, and architecture. Monks continue to carry on cenobitic life today; monasticism is especially revered in the Eastern Churches. A few of the most famous monastic traditions are:

Benedictines

Cistercians

Trappists

Carthusians

St. Francis of Assisi, by Jusepe de Ribera

Friars

In the 13th century, St. Francis of Assisi and his followers started living a form of consecrated life quite different from the monks of the time. Instead of practicing monastic stability, they travelled from place to place preaching, going wherever their superiors asked them to go. Instead of owning everything in common, they wanted to own as little as possible! This new way of life came to be called mendicant life, and its followers were simply called friars (meaning “brothers”), rather than monks. While monastic life was wholly devoted to contemplation, mendicant life was much more active, engaging in works of mercy such as caring for the sick and poor.

At nearly the same time, St. Dominic de Guzman began a similar mendicant Order, also devoted to preaching, living radical poverty, and going wherever one was sent rather than remaining in one monastery. The Carmelite Order was founded in the Holy Land around this same time; though its first adherents were hermits living on Mount Carmel, when the Carmelite Order relocated to Europe it took on mendicant characteristics. Many other mendicant orders were founded in the centuries following, and mendicant life became one of the most popular religious vocations. Mendicant traditions which still thrive today are:

Franciscans

Dominicans

Carmelites

Augustinians

Alexian Brothers

Mercedarians

De la Salle Christian Brothers

Salesians

Servites

St Ignatius of Loyola, by Peter Paul Rubens

Religious Priests

A form of religious consecration which developed out of the mendicant tradition is religious priesthood, in which ordained men take religious vows in a community of priests. Among the forms of religious priesthood, some of the most common are:

Clerics Regular, such as Jesuits and Camillians

Canons Regular, such as the Norbertines, Canons Regular of the Immaculate Conception, and Canons Regular of St. John Cantius

Secular Institutes, such as the Father Kolbe Missionaries of the Immaculata and the Schoenstatt Fathers